Painting with Clothes: How Maria Likarz-Strauss used Fashion to bring Modernism into daily life through textile design at the Wiener Werkstatte

Painting with Clothes:

How Maria Likarz-Strauss used Fashion to bring Modernism into daily life through textile design at the Wiener Werkstatte

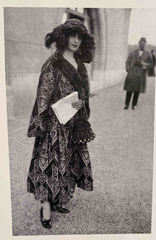

Maria Likarz-Strauss, c 1918

Maria Likarz-Strauss (1893-1971) [1] pushed the envelope of textile and fashion design by looking to modernist painters who tested the limits of representational painting, including Cubists and Symbolists, in a comprehensive way no other fashion designer had done before, and thus importantly influenced modern fashion design. Her use of contrasting shapes and colors released textile design from traditional Western European styles, which relied on stylized Victorian and Arts and Crafts motifs. Through these contrasts her textiles achieved more intensity than others, and as with Cubism in painting, these contrasts created the experience of modern life in fabric. In her approach to textile design, I believe she looked specifically to the French modern painters of the 1910s, and in doing so she brought textile design into the modern era more than any other early twentieth century textile designer.

Until 1890, progressive design in Europe, whether Art Nouveau in France, or Arts and Crafts in England, while different in each country, commonly used stylized natural forms as ornament in a rejection of classicism. Towards the turn of the century, however, as the world continued to transform through technology, social changes, and urban living, progressive artists and designers looked for new approaches to the modern world, resulting in new approaches to art and design. Vienna was at the center of this exciting new era. The Vienna Secession Movement, founded in 1897 by architect Josef Hoffman (1870-1956), artist Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) and others provided an alternative way for progressive artists to exhibit their work, which was polarizing to the established academic approach of Vienna’s Fine Arts Academy at the turn of the century. In Paris, a similar group of polarizing artists had formed the Société des Artists Independents[2] in 1884 in response to the rigid traditionalism of the government-sponsored Salon. The artists who exhibited at these Paris Salons for the next three decades pioneered the styles now associated with modernism and avant-garde art, such as Expressionist, Cubist, Abstract, Post-Impressionist, and Fauves.

Unlike the Salon des Independents, the Vienna Secession Movement capitalized on its artistic and design success by opening the Wiener Werkstatte[3], founded in 1903 by Hoffman and artist Koloman Moser (1868-1918), as an outpost where progressive artists and designers could make artistic goods for sale, ranging from postcards to furniture, ceramics, textiles and fashion design.[4] Affluent clients demonstrated their progressive taste by purchasing fashionable modern objects and clothing. Although the founders of the workshop did not specifically provide equality for female artists, Vienna was one of the few cities at the time where women had opportunities to become decorative artists, and the Wiener Werkstatte employed at one point an astounding 180 women.[5] Due to Vienna’s School of Arts and Crafts, one of the few schools which had allowed women to enroll from its founding in 1867, the Wiener Werkstatte had a consistent network of talented female students.[6] While the public had yet to embrace women as artists, and the Wiener Werkstatte did promote male artists’ work more prominently, it was still a place which gave many female decorative artists the opportunity to experiment artistically, which was unusual at the time.[7] The women artists appeared to be a happy, close knit group, as evidenced by photographs and their collaborative decorating of their workshop.

Left Image: Female artists of the Wiener Werkstatte, including from left to right Charlotte Billwiller (b.?), Mathilde Flogl (1893-1958), Susi Singer (1891-1955), Marianne Leisching (1896-1971), Likarz-Strauss, c. 1927; Thun-Hohenstein, Christoph, et al, Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstatte, p 6.

Right Image: Mural paintings by Lotte Calm (b1897-?), Lilly Jacobsen (b1895-?), Fritzi Low (1891-1975), Anny Schröder (1898-1972) and Vally Wieselthier (1895-1945) at the textile department of the Wiener Werkstätte, Kärntner Straße 32, 1918, MAK Collection

Likarz-Strauss was one of the most prolific and longest tenured artists of the Wiener Werkstatte, producing nearly 200 textile designs in her two decade career there,[8] and yet relatively little is written about her life. It is difficult to find a photograph of her, and accounts differ on her dates of employment, and even her death. [9] She was born in Poland, but is considered Austrian, studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule[10] between 1911 and 1915 and worked at the Wiener Werkstatte from 1912 to 1932.[11] As one of the most successful designers, nearly all of her designs remained in the Wiener Werkstatte product line until 1930[12]. Likarz-Strauss’ earliest fabric designs date to 1910 when she was a student of Hoffman himself.[13] She also worked in the graphics department, bags and cushions, before concentrating on fashion until 1927 when she worked in carpet and wallpaper. Unlike other fashion designs from the Wiener Werkstatte, hers were always labeled with the name of the fabric pattern she also designed, proving her success in as her clothing was allowed to be named by her own textile designs. She was also responsible for increasing sales in the fashion department. Marianne Leisching, a colleague, wrote in her memoir:

In consultation with Julius Rix, the director at the time, she had made it her business to make above all good and wearable clothes from Wiener Werkstatte fabrics. As a result, sales in the fashion department and of the fabrics grew.[14]

As a designer in the Wiener Werkstatte’s popular textile department, Likarz-Strauss would have been well aware of the art not only in Vienna but also in France. Exhibits at the Salon des Independents each year were widely reviewed and published, as the work of the Avant Garde created tensions between the old establishment thus extreme critical responses at the turn of the century. Since textile and fashion design in Vienna occurred alongside this artistic backdrop, Likarz-Strauss’s work may best be analyzed by viewing her fashion designs alongside well published paintings from the decade prior to her success. Artists of the Avant Garde in Western Europe were playing with flattening the picture plane, giving no sense of recession into the background. Likarz-Strauss picked up on these experiments with painting in her textile designs, which are clearly influenced by French paintings of the 1910’s, including Piet Mondrian’s (1872-1944) Tableau, Fernand Leger’s (1881-1955) Cubist experiments, and Robert Delaunay’s (1885-1941) plays on geometric and abstract forms of color. The best place to start this analysis is with her dress fabric, “Romulus”.

Dress Fabric, “Romulus”, 1928, Designed by Maria Likarz-Strauss; Silk, plain weave, screen printed; 49.3 x 95.3cm (19 3/8 x 37 ½ in); Produced by the Wiener Werkstätte, Vienna, Art Institute of Chicago

Design Drawing for Textile, 1928, Designed by Maria Likarz-Strauss, graphite pencil, paper, watercolor, H 29.5cm, W 23cm; Produced by the Wiener Werkstätte, Vienna, Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria

Because of the incredible collections at the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna (MAK) and the Art Institute of Chicago, it is possible (though rare) to find an existing piece of fabric and the corresponding original design sketches utilizing it. In my research, no other scholar has found the match between this drawing in the archives at the MAK and this fabric at the Art Institute. This design was clearly one of her most successful, as not only is the original textile still extant, but the original swatch card as well.

Swatch Card, of the Wiener Werkstatte fabric “Romulus” by Maria Likarz-Strauss, 1928, MAK

While it is exciting just to see fabric and fashion design side by side, each becomes richer yet when viewed in reference to Leger’s series of paintings, “Contrast of Forms”, painted a decade earlier, which Likarz-Strauss deliberately referenced in her design.

.

|

|

|

Contrast of Forms, 1913, Fernand Léger, Courtauld Gallery, London |

Contrast of Forms, 1913-1914, Fernand Leger, Philadelphia Museum of Art |

Between 1912-1914 Leger did a series of paintings of primary colors with black and white to demonstrate a composition which was not read as a narrative. Cubists had been experimenting with this concept, using mechanical shapes and painting in abstraction, not representation. Leger’s style of leaving so much blank canvas, with white applied, would have been unthinkable ten years before. Cubism was defined by breaking the typical rules, defying standards and creating its own path.[15] Leger believed that painting should be independent from its traditional role of representation, and that it could attain the “greatest possible dissonance and “intensity” by means of contrasting shapes and colors.”[16] The effect of contrast would “create in painting an “equivalent” to the experience of modern life.”[17] The defiance of typical rules given to art was a hallmarks of the cubists, and Likarz-Strauss would return to Leger for inspiration throughout her career, always using a black or white foreground to focus on shapes and colors on a flat ground, such as in the dress design below.

|

|

|

Mechanical Elements, Fernand Leger, 1918, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

Faschingskostüm (Spanierin), Maria Likarz-Strauss, Vienna, 1929, Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria

|

Another artist in France, Robert Delaunay, also experimented with abstract forms over representation in art, and explored movement on flat surfaces, simultaneously sharing his excitement for the modern world undergoing rapid technological change through art. The painting “Hommage a Bleriot” is a tribute to the first person to cross the English Channel in a plane. The movement of the lines creates a feeling of motion with no vanishing point or illusions, a technique Likarz-Strauss adopted in her use of lines meeting at angles.

|

|

|

Robert Delaunay, Hommage à Blériot, 1914, Kunstmuseum Basel. Image in public domain. |

Kostüm, Maria Likarz-Strauss, Vienna, 1930, Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria |

In the late 1920s many of Likarz-Strauss’s designs referenced other Avant Garde art movements, including the Dutch De Stijl movement, which began in 1917. Piet Mondrian was a member of this movement, and his paintings “Tableau 1” and “Tableau 2”, continue the theme of creating art which could be universally understood by people from any culture: a “pure” painting. To create these “universal” works of art, Mondrian simplified visual art to its essence and created images that reflect visual harmony. Like much of the art from this period, his flat and direct painting did not depend on illusions like depth.[18] In several pieces, Likarz-Strauss brilliantly translates this idea to clothing, with designs which are mostly white, divided by black horizontal and vertical crossing lines that frame blocks of colors. Her two designs from 1929 clearly refer to “Tableau”s, while that from 1926 references “Oval Composition”.

|

|

|

Klein aus Gaze, Maria Likarz-Strauss, Vienna, 1929 Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria |

Klein aus Wollgeorgette, Maria Likarz-Strauss, Vienna, 1929, Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria |

|

|

|

Tableau 1, Piet Mondrian, 1921, Oil on canvas, Kunstmuseum Den Haag

|

Tableau II, Piet Mondrian, 1922, Oil on canvas, Guggenheim Museum, New York

|

|

|

| Oval Composition, Piet Mondrian, 1913-14, Museum of Modern Art, New York |

Klein aus Wiener Werkstatte-Stoff "Zyprian" (original-language title); Maria Likarz-Strauss, 1926, Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria |

An analysis of the influence of Avant Garde artists on female Wiener Werkstatte textile designers must include the other Wiener Werkstatte textile artists who were influenced by Cubism and modern art, such as Camilla Birke (1905-1988), Mea Angerer (1905-1978) and Mathilde Flogl (1893-1950) among others. Yet unlike Likarz-Strauss, none of these were able to translate their art-influenced designs into actual wearable fashion. Angerer’s designs reference Picasso’s cubist still lifes in a representational way, yet they did not become wearable. Birke references Picasso’s African forms, yet her textiles, while modern, did not make the jump into production. Likarz-Strauss alone created a wearable way to bring modernism to life for women of Vienna through fashion.

|

|

|

Wiener Werkstatte -Stoff, Camilla Birke, Vienna, about 1925; tracing paper, ink and gouache

|

Wiener Werkstatte -Stoff "Mops", Camilla Birke, Vienna, before 1924, paper, ink |

|

|

|

Wiener Werkstatte-Stoff, Mea Angerer, Vienna, about 1927, graphite pencil, paper, gouache

|

Wiener Werkstatte -Stoff, Camilla Birke, Vienna, about 1925, tracing paper and gouache

|

|

|

|

Wiener Werkstatte-Stoff, Mea Angerer, Vienna, about 1927, graphite pencil, paper and gouache

|

Wiener Werkstatte -Stoff "Firmung", Mea Angerer, Vienna, 1926, graphite pencil, paper and gouache

|

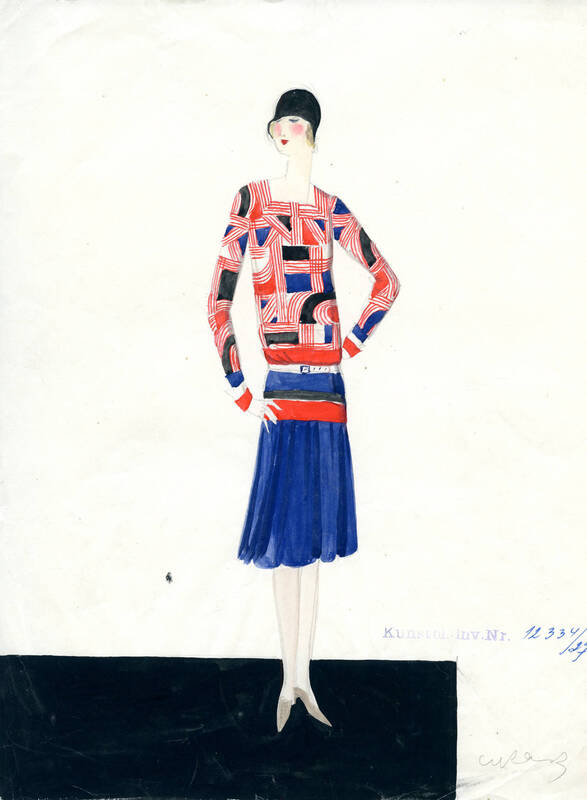

While much of the Wiener Werkstatte fashion design was clearly influenced by the French Avant Garde artists, contemporary French fashion designers in the 1920s lagged behind Austria in originality. In fact, the leading French fashion designer at the time, Paul Poiret (1879-1944), who was working on new fabric patterns with an Oriental interest, is said to have been influenced by the Wiener Werkstatte, rather than the other way around, but his designs never evolved into the incredibly modern abstract patterns of the Wiener Werkstatte. In France, the fashion capital of the world, interest in Wiener Werkstatte fabrics was minimal and any influence was associated with Poiret.[19] French fashion plates from the same years as Likarz-Strauss’s Avant Garde designs show drop-waist dresses and plain colors. Compared to the modern, abstract, cubist patterns of the Austrian designs, literally bursting with color, the French look downright boring. Unlike in Austria, these designs were not pushing the envelope for the women of France.

|

|

|

|

Art Deco French 1920s Fashion Design Vintage Print, 1928, Atelier Bachroitz |

Art Deco French 1920s Fashion Design Vintage Print, 1928, Atelier Bachroitz |

Conversely, although France led the fashion world, the Wiener Werkstatte fashion designers seemed uninterested in French fashion or any other international trends. A few small photographs of Poiret comprise the entire reference library of the Wiener Werkstatte archives, and besides those there is no proof that any Wiener Werkstatte artist showed any interest in international fashion trends. [20] Rather, the Wiener Werkstatte artists, and led by Likarz-Strauss, were influenced by art, not other fashion designers, and this is what led to a completely original style of fashion.

Paul Poiret, Fashion model, photograph from Wiener Werkstatte fashion department collection

The originality of Likarz-Strauss’s designs contributed to the sustained good reputation of the textile department at the Wiener Werkstatte, and although they were expensive and “outlandish” patterns, especially in comparison to the fashionable clothing in France of the same year, the fabrics, the largest share of which were designed by Likarz-Strauss,[21] were the most successful goods produced by the Wiener Werkstatte on an international level. I believe this is because her patterns are expressive even on a simple piece of fabric, due to her ability to reference the tenets of the Avant Garde artists at the time. Better than any fashion designer at the time, she was able to translate the language of modern art, which resonated with the fashionable elite, into clothing.

Likarz-Strauss’s completely inventive and original designs led to her success and contributed to her promotion to run the fashion department along with Max Snischeck from the mid-1920s,[22] but unfortunately for the history of fashion design, Likarz-Strauss was removed from the fashion department entirely after Director Julius Rix (b?–d.1927) died, probably due to intrigue involving herself and Rix’s daughter, Felice (1893-1967), who also worked in the textile department with Likarz-Strauss.[23]

Hilda Jesser (1894-1985), Lotte Calm (1897-?), Fritzi Low (1891-1975), Felice Rix, Group photo at the School of Arts and Crafts, ca 1916

Despite her abrupt departure from the fashion department, fabric production continued at the Wiener Werkstatte until 1929, one of the last goods to continue until its closure.[24] I believe credit for this goes to Likarz-Strauss’s successful designs, as no other woman at the Wiener Werkstatte created more fashion designs.[25]

As a leading center of progressive art and culture in the early decades of the 20th century, Vienna provided the perfect backdrop for the Wiener Werkstatte to produce goods which were a tangible representation of the contrasts, complexities and contradictions inherent in Modernism. Contrary to other countries at the time, in Vienna, through the designs of Likarz-Strauss and others at the Wiener Werkstatte, women could bring modernism into the home through fashion. Through their materiality as a flat woven plane, textiles are ideal to show the interplay of openings and spaces, the simple forms and the flattening of the picture plane for which modern artists were receiving such recognition. Textiles are important on the road to modernism as they brought modern art into fabrics proving that people were internalizing modernism at home. Likarz-Strauss led Wiener Werkstatte textile designers to incorporate the new language of modern art into clothing, for the first time making modernism part of daily lives.

Bibliography

Armstrong, Jared, and Edward Timms. “Souvenirs of Vienna 1924: The Legacy of David Josef Bach.” Austrian Studies, vol. 14, 2006, pp. 61–97. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27944801. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

“Artists & Designers - Wiener Werkstätte (1903-1932).” DMA Collection Online, collections.dma.org/essay/Va3E8DZp.

“Back Matter.” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, vol. 4, 1987. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1503964. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Blauensteiner, Kurt, and David P. Berenberg. “The Industrial Arts in Austria.” Parnassus, vol. 4, no. 5, 1932, pp. 24–26. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/770985. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Brandstatter Christian, and Brandstatter Christian. Wiener Werkstatte Design in Vienna, 1903-1932: Architecture, Furniture, Commercial Art, Postcards, Bookbinding, Posters, Glass, Ceramics, Metal, Fashion, Textiles, Accessories, Jewelry. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2003.

Brandstatter Christian, et al. Tailored for Freedom: the Artistic Dress around 1900 in Fashion, Art, and Society. Kunstmuseen Krefeld, 2018.

“Departmental Accessions.” Annual Report of the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 136, 2005, pp. 8–43. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40305358. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Dogramaci, Burcu. “Fenster Zur Welt. Künstlerische Modegraphik Der Weimarer Republik Aus Dem Bestand Der Kunstbibliothek Zu Berlin.” Jahrbuch Der Berliner Museen, vol. 45, 2003, pp. 201–233. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4423761. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Fahr-Becker, Gabriele. Wiener Werkstatte 1903 - 1932. Taschen, 1994.

“Front Matter.” Parnassus, vol. 4, no. 5, 1932, pp. 17–26. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/770974. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

“Front Matter.” The Print Collector's Newsletter, vol. 9, no. 4, 1978. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44130441. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Hess, Heather. “Changing Impressions: Wiener Werkstätte Prints and Textiles.” Art in Print, vol. 1, no. 3, 2011, pp. 19–26. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43045223. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Houze, Rebecca. “At the Forefront of a Newly Emerging Profession? Ethnography, Education and the Exhibition of Women's Needlework in Austria-Hungary in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Design History, vol. 21, no. 1, 2008, pp. 19–40. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25228564. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Klesse, Brigitte. “Museum FÜr Angewandte Kunst (Kunstgewerbemuseum) KÖln.” Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, 48/49, 1987, pp. 526–529. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24660694. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Long, Christopher, and Peter Noever. The Burlington Magazine, vol. 145, no. 1203, 2003, pp. 458–459. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3100737. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Loring, John. “Postcards of the Wiener Werkstaette.” The Print Collector's Newsletter, vol. 9, no. 4, 1978, pp. 105–108. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44130442. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

“Maria Likarz-Strauss.” Maria Likarz-Strauss | People | Collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, collection.cooperhewitt.org/people/51685419/.

“Maria Likarz.” The Art Institute of Chicago, www.artic.edu/artists/35487/maria-likarz.

The Museum of Modern Art. “Fernand Léger, Contrast of Forms.” Smarthistory, smarthistory.org/fernand-leger-contrast-of-forms/.

Pabisch, Peter Karl. “The Uniqueness of Austrian Literature: An Introductory Contemplation on Heimito Von Doderer.” Chicago Review, vol. 26, no. 2, 1974, pp. 86–96. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/25303146. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Petrulis, Alan. “L - ARTISTS.” MetroPostcard List of Postcard Artists and Illustrators L, www.metropostcard.com/artistsl.html.

Philadelphia Museum of Art. “Contrast of Forms.” Philadelphia Museum of Art, www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/51039.html.

Rayner, Geoff. Jacqueline Groag: Textile & Pattern Design. ACC ART Books, 2019.

“Recent Important Acquisitions: Made by Public and Private Collections in the United States and Abroad.” Journal of Glass Studies, vol. 40, 1998, pp. 141–179. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24190507. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Schoeser, Mary, and Angela Völker. “Art into Industry.” RSA Journal, vol. 143, no. 5461, 1995, pp. 92–93. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41376813. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

“Tableau II, 1922 - by Piet Mondrian.” Tableau II, 1922 by Piet Mondrian, WWw.piet-mondrian.org/tableau-ii.jsp.

Terraroli, Valerio, and Patricia Brigid Garvin. Ver Sacrum: the Vienna Secession Art Magazine, 1898-1903: Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Otto Wagner, Alfred Roller, Max Kurzweil, Joseph M. Olbrich, Josef Hoffmann. Skira, 2018.

Thun-Hohenstein, Christoph, et al. Die Frauen Der Wiener Werkstatte = Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstatte. MAK, 2020.

Von Wilckens, Leonie, et al. Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 54, no. 1, 1991, pp. 141–143. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/1482525. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Volker Angela, and Ruperta Pilcher. Textiles of the Wiener Werkstatte, 1910-1932. Thames & Hudson, 2004.

Witt-Dorring Christian, et al. Wiener Werkstatte 1903-1932 the Luxury of Beauty. Prestel, 2017.

“Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstätte.” ARTLECTURE_Contemporary Art Platform, artlecture.com/article/1648.

Zerner, Henri, et al. “Notes.” Print Quarterly, vol. 17, no. 4, 2000, pp. 391–412. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41826197. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

[1] Maria Likarz-Strauss is referred to throughout scholarly sources as “Maria Likarz-Strauss,” “Maria Strauss Likarz”, “Maria Strauss-Likarz”, or “Maria Likarz”. I refer to her as Maria Likarz-Strauss, according to the Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna.

[2] Translated in English as Society of Independent Artists.

[3] Translated in English, “Vienna Workshops”.

[4] Excerpt from Kevin Tucker, Dallas Museum of Art unpublished material, “Modern Opulence in Vienna” gallery text, “Jugendstil and the Wiener Werkstätte,” 2014.

[5] Thun-Hohenstein, Christoph, et al. Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstätte. MAK, 2020, 7.

[6] Ibid, 7.

[7] Ibid, 9.

[8] “Maria Likarz-Strauss.” Maria Likarz-Strauss | People | Collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, collection.cooperhewitt.org/people/51685419/.

[9] The Art Institute of Chicago lists her date of death as 1956.

[10] The Vienna School of Arts and Crafts, founded in 1863, now the University of Applied Arts Vienna.

[11] The Cooper Hewitt website states her dates of employment from 1912-1932, although there are conflicting dates; for instance, the website “Beloved Linens” States her date of employment as 1920-31; and “Metropostcard” states that she moved to Rome in 1928 to work on ceramics.

[12] Thun-Hohenstein, Christoph, et al. Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstätte, 105.

[13] Ibid, 105.

[14] Leisching, Marianne, reports on the Wiener Werkstatte (manuscript), Amsterdam 1959, MAK, Wiener Werkstatte Archive, WW MANU 1, quoted in Thun-Hohenstein, Christoph, et al. Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstätte, 105.

[15] The Museum of Modern Art. “Fernand Léger, Contrast of Forms.” Smarthistory, smarthistory.org/fernand-leger-contrast-of-forms/.

[16] Philadelphia Museum of Art. “Contrast of Forms.” Philadelphia Museum of Art, www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/51039.html.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Tableau II, 1922 - by Piet Mondrian.” Tableau II, 1922 by Piet Mondrian, WWw.piet-mondrian.org/tableau-ii.jsp.

[19] Volker, Angela, Textiles of the Wiener Werkstatte, 1910-1932, 203.

[20] Ibid, 205.

[21] Volker Angela, “Fashion Textiles and wallpaper,” in Witt-Dorring, Christian/Staggs, Janis (eds), Wiener Werkstatte 1903-1932, The Luxury of Beauty, exh. Cat. Neue Galerie, Munich/London/New York, 2017, 265.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid, 105.

[24] “ Wiener Werkstatte in Berlin,” in: Vossische Zeitung, 31 Oct 1929, quoted in: Rainer, Paulus, “Eine Chronologie der Wiener Werkstatte,” in: Noever, Peter (ed.), Der Preis der Schonbeit. 100 Jabre Wiener Werkstatte , Ostfildern-Ruit 2003, 385 f., quoted in Thun-Hohenstein, Christoph, et al. Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstätte.

[25] Ibid, 265.