The True Hollywood Star: The Work and Legacy of Paul R. Williams

The True Hollywood Star: The Work and Legacy of Paul R. Williams

By Kathryn Davis

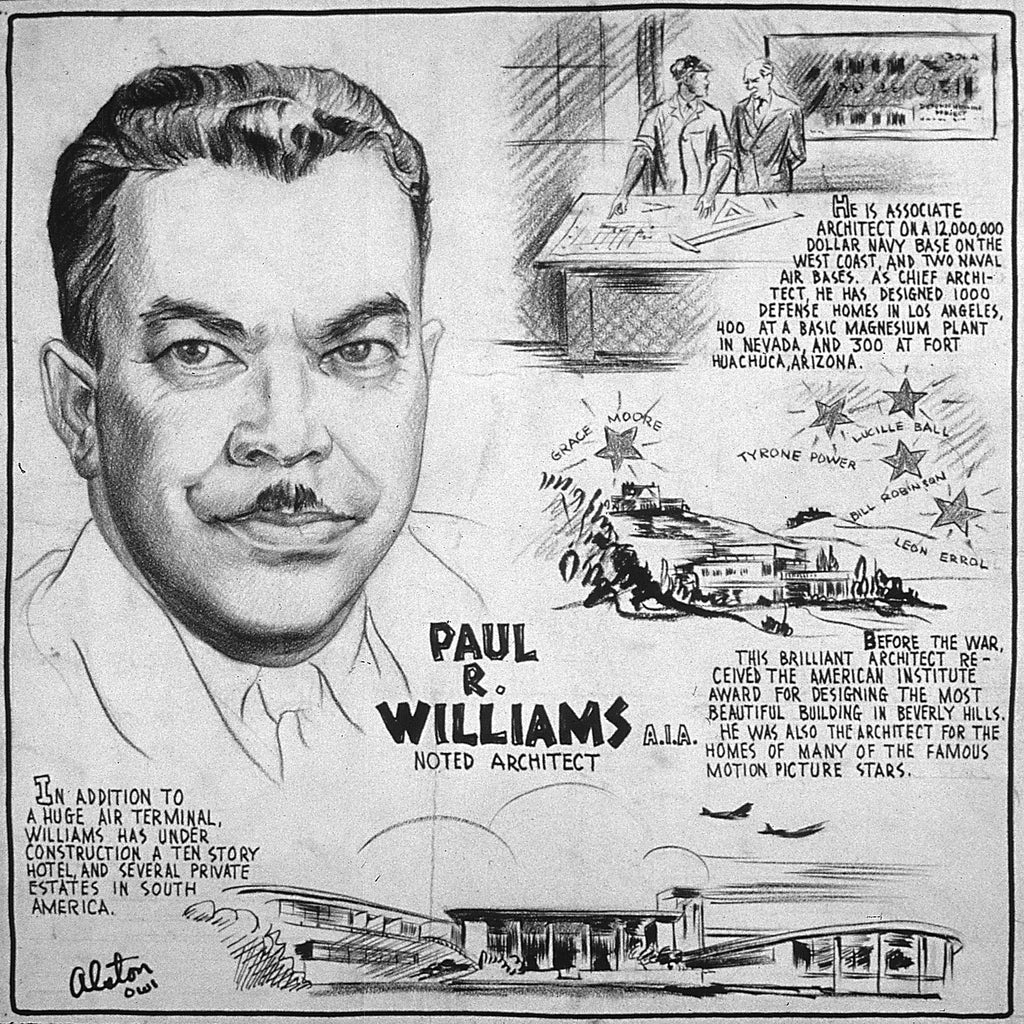

Frank Sinatra; Lucille Ball; Howard Hughes; Sharon Tate; the Beverly Hills Hotel: These all represent exciting and well-known names and stories in the Hollywood lexicon. Yet the man who connects them (more on that later) has remained relatively unknown except in elite architectural circles, like the AIA board. In fact, the one building this man IS known for, the TWA terminal at LAX, he had nothing to do with designing! (It was actually designed by Gin Wong of Luckman & Pereira).[1]

Paul Williams in front of the Theme Building at LAX Airport (FN US Modernist.org)

How did this happen? In this paper, I will show how the work of black architect Paul Williams (1894-1980), with his extraordinary five-decade career, is far more relevant to the architectural history canon than is demonstrated by his representation within it. Without question, his contributions should be more widely recognized for his influences on both architecture and interior design. An analysis of Williams’ work reveals a sad truth about the field of architecture: not only are black architects underrepresented in their field, those black architects are not as recognized nor celebrated for their achievements compared to white contemporaries. Based on his work, Williams should be better known and better represented in the standard canon of trailblazing architects. Shockingly, Williams participated in some 3000 projects over the course of his life, and yet was awarded the AIA Gold Medal only in 2017, almost 40 years after his death.[2]

To begin, not only did Williams persevere in architecture in a difficult historical era for a black man, but he overcame significant personal tragedies to do so. Both his parents died of tuberculosis, his father when he was two and his mother when he was four.[3] He was placed in a separate foster home from his brother, with Mr. and Mrs. C. I. Clarkson. In 1908, he graduated with honors as the only black child in his entire elementary school.[4] At this time, Los Angeles was 36th in the nation based on population but only 3131 out of 102,000 residents (3%) were black.[5] At Polytechnic High School, a teacher counseled him not to be an architect because no white clients would want him and there weren’t enough black clients to afford one.[6] When he did get married, his first son, Paul Revere Williams Junior, died before reaching one year of age. Yet Paul Williams persevered in the face of racism and his personal tragedies not only to successfully navigate school but also to become a well-recognized, professionally respected architect. Despite his teacher’s horrible advice, he became certified as a building contractor in 1915, a licensed Californian architect in 1921, opened his own practice, and became the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1923.[7]

During the 1920s, California’s real estate boom ignited, during which time, Williams gained a reputation as a skilled designer of small, affordable houses which led to commissions for historical revival-style homes for wealthier suburban clients.[8] An example is the Franchon Beerup house in Beverly Hills, designed in 1929, and one of his earliest homes to be featured in Architectural Digest. An interesting aside, this home was made famous when Howard Hughes crashed his plane into it in 1946, destroying the house.

Franchon Beerup House, post-crash and rebuilt, PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

Williams also designed buildings connected to other Hollywood names: the house that Sharon Tate famously rented; two homes for Lucille Ball; and a renovation of the Beverly Hills Hotel, all of which helped cement his reputation in Hollywood circles.

1941, Lucy and Desi Arnaz Ranch, aka Desilu Ranch, Charsworth, CA, PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

1954, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz House, Rancho Mirage, CA (the Arnaz’s moved to the new location because Desi won the lot in a poker game); PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

During the depression, Williams smartly focused on the movie industry clients, creating a niche that was immune from an economic downturn. He seemed to know the styles that Hollywood wanted “instinctively”.[9] While other architects found themselves out of work, Williams received the commission in 1934 for Jay Paley’s Bel Air home. Remarkably, he had already completed 36 other significant Hollywood homes by that time. He had established his reputation as the “architect to the Hollywood stars”[10] thanks to his thoughtful and intelligent responsiveness to his clients’ needs.

Williams continued to design residential homes in varied revival styles throughout the 30s and 40s, but he also continued innovating and thinking broadly about architecture. In World War II, he realized post-war America would demand stylist, affordable housing and authored two pattern books. In 1945, he published Small Homes of Tomorrow, and in 1946, Homes of Today. In these books, he was almost radical in his ability to translate his luxury homes featuring wildly different revival styles into simple, easily patternable homes for middle class housing.

My copies of the reprinted pattern books by Paul R. Williams

The homes he develops in these books are named after styles of architecture as diverse as “English Country” to “Mexico City” to “Miami”, which he adapts for small modest homes.[11] The sheer diversity of style and ability to translate many varied styles to something accessible to the masses is remarkable.[12] He writes in his book:

An eager generation of young people coming out of the war is filled with the desire to have homes of their own- and homes of their own building and planning… “What will the new homes be like? What are the labor-saving and beauty-enhancing innovations being prepared for us …?” … There is a question in the minds of many people as to what is meant by good modern architecture, and rightly so.[13]

In recognizing an opportunity to help this generation, he wanted to make beautiful homes and different styles accessible. He wanted the masses to have access to all his designs regardless of budget, another example of his radical way of thinking. He is perhaps the only architect to boldly name a small, 2500-foot home design “The Versailles”.[14]

The Small Home of Tomorrow, Williams

And yet the majority of his residential clients were the crème de la crème of the famous Hollywood elite. He was widely published in Architectural Digest. Just counting from his home designs, of which I reviewed hundreds, I counted over 40 published in the 1950s alone.[15]

In reviewing the large canon of Paul Williams (over 2000 private homes designed in the Los Angeles area!), certain stylistic and modern elements become apparent, some of which we, as designers, automatically link to other architects, but which actually first appear in earlier homes designed by Williams. Additionally, he pioneered the idea of working together as an interior design team throughout a project starting with the initial programmatic planning. His insistence on collaboration with all the decorators who worked on his projects proves that he was always concerned with the client’s use of the home. He said: “To be sincere in my work, I must design homes, not houses.”[16] As the architect, it was unusual at the time to think of the work as an integrated whole, including furniture plans of rooms. Although sadly many have been demolished, there are still many existing homes that represent his architectural contributions.

Williams was a master at mixing revival styles. His oeuvre includes examples of Colonial Revival, Spanish Revival, Neo-Classical, Greek Revival, Georgian Colonial Revival, and also included Art Deco, Baroque and Mid-century modern. The Jay Paley house, from 1936, is a good case study, a mix of Colonial and Baroque, with some Neo Classical and Art Deco thrown in. Streatfield writes “Williams design for the Paley estate appears traditional but his treatment was decidedly modern”.[17] Mixing all these elements makes it so. The home is designed with traditional Georgian elements, but the furniture is modern. The Paley house is also an example of working closely with the decorator, Harriet Shellenberger. The beautiful hand drawing for the entrance is very art deco while the interior decoration is baroque and neoclassical. The client had specific lifestyle requirements, including outdoor living, and Williams designed for this program which was itself a modern take on architecture.

Hand drawn site plan and plan for the entry court, Houses of Los Angeles

Houses of Los Angeles, Georgian Colonial façade and interiors

Along with collaborating with decorators, he was also an early innovator in the field of interior design. In The Small Home of Tomorrow, in 1925, he innovated “The Kitchen of Tomorrow”, designing a plan which looks exactly like an ideal modern kitchen today. He wrote:

A friendly workspace which conveniently contains the latest devices for the preparing of food is the formula for tomorrows kitchen. The popular kitchen will develop a better use of the horizontal wall space … It remains to plan a horizontal refrigerated food space, table level recessed electric overs and dish and pan storage next to the dishwasher.”[18]

Williams invented the refrigerator drawer and the drawer microwave decades before sub-zero did. This type of open plan and organization evolved a completely new way of thinking.

The Small Home of Tomorrow, Kitchen Plan

He was still innovating in 1970. In Frank Sinatra’s home, he invented what may be the first residential use of roller shades and automated doors.[19] This home is a wonderful example of midcentury architecture but is now torn down.

The Frank Sinatra House, 1955, Bev Hills, CA (Williams daughter, Norma, is in the photo with Williams and was the interior designer of the home), PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

Other styles Williams repeated explored in his designs include American Colonial Revival, using symmetry and balance with thin columns on the façade, and Greek Revival, adding elements like classical wood pilasters, dentilled moldings and a curved broken pediment.

Preminger House, 1925, LA Times, Home Tours

He designed equally skillfully in the Spanish Colonial style, and in brick, stucco, and wood. He excelled at designing with wooden beams on the exterior and interior.

- W. D. Hallett House, combining arches, Spanish tile, and wooden beams; LA. PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

On the interior, he loved to use arches. For example, the Harke House is a traditional brick home with several interior arches. The home features the thin symmetrical columns present in much of his exterior design.

The Christian and Marjorie Harke House, 1930, Beverly Hills, PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

Williams also explored modernism including the use of pilotis, like Le Corbusier, which he incorporated in his own home in Los Angeles.

1952, Paul R and Della Williams House, Los Angeles CA, PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

In the last decade of his practice, his designs continued to be as diverse as modern tract houses and French chateaus.

1960, Seaview Palos Verdes Tract Houses, Palos Verdes, CA, 190 houses; PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com[20]

1971, last known design, Richard and Marjorie Jackson house, Beverly Hills, CA, PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

Paul Williams accomplished all of this while confronting extreme racism in Los Angeles and from within his profession. Remember, as a child, his teacher discouraged him from going to architecture school. A mentor told him there wouldn’t be enough wealthy black people in LA for him to stay in business, implying of course that a white person would never hire a black architect. Williams remarked at the irony that many of the homes he designed were on land still governed by segregation deeds.[21] He spoke about how he had to learn to sketch upside down because the clients were uncomfortable sitting on the same side of the table as he.[22] What I find most important, and remarkably not quoted nor reprinted anywhere today, is an essay he wrote for the 1937 edition of The American Magazine, entitled “I Am A Negro”:

I came to realize that I was being condemned, not by lack of ability, but by my color. I passed through successive stages of bewilderment, inarticulate protest, resentment, and, finally, reconciliation to the status of my race. Eventually, however, as I grew older and thought more clearly, I found in my condition an incentive to personal accomplishment, and inspiring challenge. Without having the wish to “show them,” I developed a fierce desire to “show myself.” I wanted to vindicate every ability I had. I wanted to acquire new abilities.[23]

In this era, these are the names of famous architects and designers that spring to mind: Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1859), Alvar Aalto (1898-1976) and Richard Neutra (1892-1970). Williams was well known to these famous contemporaries, for not only did Williams collaborate with decorators but in fact, Williams designed with some of these architects who hold places of honor in history. In 1941 he designed a housing project with Neutra, and in 1948 he designed a house with a student of Frank Lloyd Wright’s. Williams named a home in his 1926 pattern book after his friend Neutra.

Williams, Small Home of Tomorrow, p. 66

What do these other names have in common? They are white. These men worked together, yet when we think of award-winning architects, we don’t think of them including Paul Williams. Frank Lloyd Wright won the AIA Gold Medal in 1949, during his lifetime; Aalto won it in 1963; Neutra won it in 1977, 40 years before Williams. When we think of landscape and siting, we think of Frank Lloyd Wright, yet Williams also paid unique attention to the siting of the homes, always making the most use of the outdoor landscape. When we think of groundbreaking interior designers, we think of Dorothy Draper, Albert Hadley, David Hicks, yet Paul Williams was equally accomplished as an early interior designer. His extensive use of wood paneling, interior arches, wooden ceilings, wooden beams of the exterior, roller shades, are all interior design features we now take for granted. We think of Dorothy Draper’s staircase at the Greenbriar as iconic, yet Williams is the first designer to use this design element as a feature in a home. He was a master at staircases, and wooden interior elements, and used them both throughout his career:

1932, David and Ida Rubin house, (left) and 1938, Charles J and Alice Correll House, Maison due Soleil, LA, Arc Digest 1938 (right) PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

1938, Gladys Collins Lehman House, Toluca Lake, CA, (left) and 1941, Brian Foy and Vivian Edwards House, LA, CA, (right), PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980); PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

1941, Bert and Mildred Lahr Estate Bev Hills, also featuring wooden beams, another feature of Williams’ interiors, PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

1932, Wood paneling, Errett Lobban Cord House, Cordhaven, Beverly Hills, Architectural Digest 1935, (Destroyed in 1963 for a subdivision)

1938, Robert J and Fritzi Fulton House, Beverly Hills, CA; PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

When I think of Paul Williams legacy, many design features come to mind, including his architectural innovations in mechanized doors and windows; striking spiral entrance staircases; patios designed as the continuation of the living room, bringing the indoors out; concealed sliding doors which bring the outside in; clever ways of using the landscape and siting the house to maximize the location and the property. Although Williams designed many incredible residential homes, a third of his work during his lifetime was commercial, including hotels, churches and retail. He also designed government projects, including several housing projects, like the Hacienda Village Housing Project in 1942, (the same year he was working for celebrities like Lucille Ball), and the Carver Manor Housing Project 1949 (when he was simultaneously designing the Tevis and Colleen Morrow House in Pacific Palisades, featured in AD the same year).

Hacienda Village Housing Project in 1942, and Carver Manor Housing Project 1949, PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

The Tevis and Colleen Morrow House in Pacific Palisades, 1949, (note the similar rooflines and windows to the Carver Manor project of the same year), PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

His contributions span the gamut and he had contributions to each area in which he designed. He leaves a legacy of innovative interior design and elegantly proportioned residential design, and of a social consciousness and contribution to society at all levels. Yet his most important legacy is how he, as a black man in a racist society, persevered through this society to become well educated, successful and well respected, all on his own. As he wrote in his essay, he was motivated by a desire to “show myself” not to “show them”.[24] Another aspect of his life is that he truly loved his career. In 1967, on the brink of retirement, he contributed to an essay called “If I were young” where he stated that he “truly loved architecture”.[25] I think that loving what he did made him able to persevere in the face of racism to accomplish the many things he did. Rather than focusing on the negative, he did what he loved, and excelled.

In conclusion, how is it that I, as an art history undergraduate major at Harvard, who took a course in architecture, never had heard of Paul R. Williams until writing this assignment? Black architects have been overlooked by those writing the canon, and we, in the interior design field, should be working to change that. When I think about what he endured, drawing upside down not to make his clients uncomfortable, while never complaining that actually they were the ones making HIM uncomfortable by putting him in the position, I think we as designers need to do more to honor the groundbreaking steps he took to emerge as a successful black architect. In 2015, more than 90 years after Williams became the AIA’s first black member, the AIA black membership is still less than 2%.[26] As of 1999, black enrollment in Schools of Architecture was on the decline, with only 2.4% of students at top schools being black.[27] I think studying these overlooked architects, identifying their contributions to the canon which may have been attributed to others, is an important first step in educating the new generations of designers so that Paul William’s remarkable attitude towards his treatment in his career, and his patience which opened the door and paved the way for more black architects, is celebrated and was not in vain.

Bibliography

Bates, Karen Grigsby. “A Trailblazing Black Architect Who Helped Shape L.A.” NPR, NPR, 22 June 2012, www.npr.org/2012/06/22/155442524/a-trailblazing-black-architect-who-helped-shape-l-a.

Budds, Diana. “The Overlooked Legacy of Pioneering African-American Architect Paul Revere Williams.” Fast Company, Fast Company, 28 Aug. 2018, www.fastcompany.com/3066503/the-overlooked-legacy-of-pioneering-african-american-architect-paul-revere-williams.

Crotta, Carol. “Architecture of Paul Revere Williams, Born 120 Years Ago, Still ‘Remarkable.’” Los Angeles Times, 19 July 2014.

“The Declining Enrollments of Blacks in Schools of Architecture.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 23, 1999, p. 35., doi:10.2307/2999294.

Discover Los Angeles. “Paul R. Williams: Architect to the Stars.” Discover Los Angeles, 6 Feb. 2020, www.discoverlosangeles.com/things-to-do/paul-r-williams-architect-to-the-stars.

“Gold Medal.” The American Institute of Architects, www.aia.org/awards/7046-gold-medal.

Hudson, Karen E. Paul R. Williams, Architect: a Legacy of Style. Rizzoli International, 1993.

Hudson, Karen E. The Will and the Way: Paul R. Williams, Architect. Rizzoli, 1994.

Hyland, Jeff. The Legendary Estates of Beverly Hills. Rizzoli, 2008.

“Paul Revere Williams Project.” Paul Revere Williams, www.paulrwilliamsproject.org/.

“PAUL REVERE WILLIAMS, FAIA (1894-1980).” USModernist, usmodernist.org/pwilliams.htm.

Robinson-Jacobs, Karen. “This Architect of Classic Hollywood Gets His Own Star Turn.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 6 Feb. 2020, www.latimes.com/business/real-estate/story/2020-02-06/architect-paul-williams-documentary.

Streatfield, David C. California Gardens: Creating a New Eden. Abbeville Press, 1994.

Watters, Sam. Houses of Los Angeles. 1920-1935. Acanthus Press, 2007.

Williams, Paul R. New Homes for Today. Murray & Gee, 1946.

Williams, Paul R. The Small Home of Tomorrow, 1945. Publisher Not Identified, 1945.

Williams, Paul Revere. “I Am A Negro.” Ebony, Nov. 1986, pp. 148–150.

[1] Paul Revere Williams, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

[2] “Gold Medal.” The American Institute of Architects, www.aia.org/awards/7046-gold-medal.

[3] Paul Revere Williams, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

[4] Paul Revere Williams, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

[5] “Paul Revere Williams Project.” www.paulrwilliamsproject.org.

[6] Paul Williams, I Am A Negro (Ebony, 1986), p. 148.

[7] “Paul Revere Williams Project.” www.paulrwilliamsproject.org.

[8] “Paul Revere Williams Project.” www.paulrwilliamsproject.org.

[9] Watters, Houses of Los Angeles (Acanthus Press, 2007), 220.

[10] Discover Los Angeles (Feb 2020).

[11] Williams, The Small Home of Tomorrow.

[12] He names the patterns “The Bermuda”, “The Regency”, “The Monterey”, “Shangri-La Cottage”, “The City House”, “The New Orleans”, “El Rancho”, “The Devonshire”, “The Embassy”, “The Louisiana”, “The Riviera”, “Town House”, “The Suburban”, “Contemporary (1-7)”, “The San Fernando”, “Hollywood Retreat,” “The Miami”, “Modernized Period”, etc., in Williams, The Small Home of Tomorrow.

[13] Ibid, p. 3.

[14] Williams, New Homes for Today, 35.

[15] Paul Revere Williams, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

[16] Discover Los Angeles (Feb 2020).

[17] Streatfield, California Gardens, p. 123.

[18] Williams, The Small Home of Tomorrow, p.90.

[19] Paul Revere Williams, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com.

[20] Unbelievably, owners in Seaview have tried unsuccessfully to secure historic preservation status for these homes. Paul Revere Williams, FAIA (1894-1980), U.S.Modernist.com

[21] Bates, A Trailblazing Black Architect Who Helped Shape L.A.

[22] Crotta, Architecture of Paul Revere Williams, born 120 years ago, still ‘remarkable’.

[23] Williams, I Am A Negro, p. 152.

[24] Williams, I Am A Negro, p. 152.

[25] “Paul Revere Williams Project.” www.paulrwilliamsproject.org.

[26] Crotta, Carol. “Architecture of Paul Revere Williams” (Los Angeles Times, 19 July 2014).

[27] “The Declining Enrollments of Blacks in Schools of Architecture.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 23, 1999, p. 35