Frederic Church and the Early Trips to Mount Desert Island, Part I

Frederic Church and the Early Trips to Mount Desert Island, 1850-1852

PART I

Introduction

Over the course of 12 years, Frederic Church made summer sketching trips to Mount Desert Island, Maine. They occurred during the period of his greatest success as the leader of the second-generation Hudson River School from 1850 to 1862. Giving Americans a sense of pride in their own national geography at a time when defining a national identity separate from Europe was so important, his easel paintings based on the summer sketching trips to Mount Desert Island made the Maine coast famous and show Church at his most "American" in his landscape painting.

Judging from his prolific sketches and the entries in the logbooks of his traveling companions, Church clearly enjoyed visiting Mount Desert Island in his first decade as an established painter, and conversely his paintings from Mount Desert Island helped make him famous. He went there eight times in the 1850s, and then continued going to inland Maine into the 1880s. Most scholars point out that he went to Maine twenty odd times throughout his life. But it is an important distinction that while he continued to love Maine and its scenery for his sketching trips, he ceased going to Mount Desert Island in favor of Mount Katahdin and the lakes in 1862, the year of his last great painting from Mount Desert Island, Coast Scene, Mount Desert (1863, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford).[1]

Church said that he just painted what he liked and what he saw. He was encouraged to draw as a diversion only; he never meant to pursue this avocation as a career. Still, following his training with Thomas Cole from 1844-1848, he was drawn to a religious aspect in his work. Scholars often try to see this religious quality in works from his mature years when he was painting on his own, after Cole. This would seem to be an exaggeration of his intentions. It is certain that Church painted what he did in great part because he enjoyed the scenery and being in the places where he viewed and saw such scenery. In these early trips to Mount Desert Island, and the hundreds of sketches on location from the island, we see Church the person- funny, spontaneous, and free- in a different way than he ever allows to show post 1862. The sketches are rich with his personality, flowing through in light quick lines.

Approach to the American Wilderness

Church is often described as portraying manifest destiny in his depiction of the great American wilderness in the period of expansionism. This notion appealed to the American public at the time, and the association with nationhood might well be why his early pictures were so critically acclaimed, and why he rose to fame so quickly after Cole's death. But many scholars feel that Church consciously intended to glorify America's expansionism through deliberate representation of the great American wilderness.[2] It can be argued, however, that Church simply loved painting the wilderness, knew what was successful for the public, and above all was an avid adventurer. It is important to remember that unlike his fellow artists of the Hudson River School, like Bierstadt, Church never followed American expansionism out West. Rather he went to South America, Latin America, the Middle East, and Mexico, and made these countries' wilderness as famous as that of his own country. His focus was never simply on glorifying America, but on glorifying nature and the world in all its diverse forms. Throughout the period of his trips to Maine and Mount Desert Island, his paintings from these exotic lands were equally famous and often more critically acclaimed than those of the land at home. To a generation without color photography, his canvases of the Cordilleras, Cotopaxi, and especially The Heart of the Andes (1859, oil on canvas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) helped speed his trajectory to fame by offering to the public a glimpse of a world unknown.

Cole's Influence: Probing for the Picturesque, the Sublime, the Nationalistic, and the Patriotic

In 1847 Church exhibited five landscape paintings at the American Art Union, and two at the National Academy. He began to receive lengthy reviews and positive criticism. His landscapes came at an opportune time. First of all, there was a growing demand among the public for paintings, unlike the conditions of private patronage that almost exclusively existed when Cole began to paint. The Art Union was gaining recognition, and its system of purchasing works for distribution by lottery for the members was a new and democratic way of purchasing art which facilitated the distribution and popularizing of Church's works. His first successes dealt with the American landscape at a time when expansionism and the civilization of landscape was foremost in the public's minds.

When Church first began painting the countryside, he chose areas where the wilderness had been tamed. He often purposely depicted wilderness areas with cultivation. Franklin Kelly, a Church historian, points out that in Church's depictions of New England, American nature had been "adapted and modified," but not destroyed. The cleared fields of New England picturesquely interspersed with hills and forests did not threaten the wilderness but proved a "romantic nostalgia" for the primeval forest.[3] This cultivation was not threatening because it was recognizable to the American public, who responded favorably to Church's landscape paintings which contained some trace of man and civilization.

For Thomas Cole, who came to landscape painting with a background in the European picturesque, depicting a nostalgia for the wilderness became part of his American vocabulary in Arcadian-like landscapes of the Catskills. Church certainly learned from Cole an awareness of the issues of disappearing wilderness, civilization, and national identity facing America through its land.

At the time Church came into the public spotlight, this question of depicting the vanishing wilderness was a major concern for critics of American landscape paintings as well. The critics for The Literary World called for a national art that celebrated wilderness, in a statement which appeared in a review of the annual exhibition of the National Academy in which Church had two works:

We wish it were in our power to impress it up on the minds of our landscape painters, particularly, that they have a high and sacred mission to preform; and woe betide them or their memories if they neglect it. The axe of civilization is busy with our old forests, and artisan ingenuity is fast sweeping away the relics of our national infancy.[4]

Church’s career shows that no social or political themes were rarely if ever foremost in his composition. Yet as a landscape painter he was faced with the decision of painting wilderness or civilization, or of composing his pictures according to a combination of the two. As a painter, he had the license to emphasize one aspect over the other, and he oscillated early on between depictions. Kelly rightly states that the majority of the landscapes he exhibited in the early years for the public and critics almost always included houses, mills, animals and human figures. Yet Kelly goes too far in stating that Church deliberately sought out places already visited by the "axe of civilization."[5]

On the contrary, his early trips to Maine show him grappling with his attitude toward the national landscape, but they show his resolve in concentrating on painting the wilderness, and they show Church continuing to return to an area famed for its unique wilderness and landscape formations, Mount Desert Island. In his early paintings of the island, Church did occasionally "civilize" the landscape by including houses or people, but as he neared the end of his time there and resolved his feelings towards the wilderness, he moved away from Cole's nostalgic and picturesque scenery toward pure brutal wilderness, beginning with The Wreck (1852, oil on canvas, The Parthenon, Nashville, TN) and Twilight, "Short Arbiter 'Twixt Day and Night" (1850, oil on canvas, The Newark Museum). Church's grappling with these conflicting representations and his final resolution of them in order to come into his full maturity as a painter occurred on Mount Desert Island and can be seen happening in such conflicting representations as The Wreck and one of his most famous oil paintings from Mount Desert, Beacon, Off Mount Desert Island (1851, oil on canvas, private collection).

The First Three Trips to Mount Desert Island

In 1850 Church took his first trip to Mount Desert Island, accompanied by two New York colleagues, Richard W. Hubbard, who had traveled there the prior year, and Regis Genoux, a fellow painter. From this first trip Church produced four canvases, all developed later in his studio in New York from the many sketches and drawings he made on his trip around the island. This was Cole’s habit, and it became Church’s too. Most landscape artists followed the pattern of taking summer sketching trips, during which they filled many sketchbooks with drawings of New Hampshire, Maine, or the Hudson River, and then spent the winter months in their studios composing easel paintings from the drawings. It was rare to paint an actual painting in front of nature itself. Church would often make small sketches, with oils as well as with graphite, and many of these sketches in both oil and graphite survive to this day.

Church liked to describe names and people through cartoons and often illustrated his letters with cartoons. One such letter at Olana shows clearly Church's feelings of awe towards Mount Desert Island upon his first trip there. On 17 August 1850, Church wrote about his first trip to Aaron Goodman, a childhood friend with whom he corresponded for the rest of this life. This letter gives a sense of Church's feelings for Mount Desert at the time of his first visit there: "Schooner Head is magnificent both inland and seaward."[6] He also sent a series of unsigned letters to the Art-Union Bulletin in which he praised Schooner Head and the area around the Lynam Farm:[7]

We were out on the "rocks" and "peaks" all day. It was a stirring sight to see the immense rollers come toppling in, changing their forms and gathering in bulk, then dashing into sparkling foam against the base of old "Schooner Head," and leaping a hundred feet into the air. There is no such picture of wild, reckless, mad abandonment to its own impulses, as the fierce, frolicsome march of a gigantic wave. We tried painting them and drawing and taking notes of them, but cannot suppress a doubt that we shall neither be able to give actual motion nor roar to any we may place upon canvas.[8]

There are few primary documents of Church's own reaction to the island, but his letter to Goodman and to the Art-Union Bulletin from 1850, combined with a few letters and contemporary sources about his reaction to Moosehead lake and inland Maine, define a man with a great sense of humor, an ability to laugh at himself, and a great love of camping and adventure. Tracy's diary and the previously unknown sketches confirm this impression, previously formed from the limited number of discovered existing sources. With the diary filling a large gap, now, and for the first time in criticism of Church in Maine, the primary sources I have had access to span the entire time he was there, however sparsely. These primary sources include the letter from 1850, the anonymous submission to the American Art-Union Bulletin, cartoons from Moosehead Lake from 1852, Tracy's "Log Book" from 1855, Church's own cartoons of their expedition, Winthrop's account of their trip in 1856, and another cartoon probably from his honeymoon on Mount Desert in 1860.

In 1851, Church again traveled to Mount Desert Island in the summer, with good friend and wealthy entrepreneur Cyrus Field. The visit to Mount Desert Island was brief, as the primary destination of their six-week trip was Grand Manan Island in the Bay of Fundy. On their return at the end of August they visited Mount Desert Island, which may perhaps be the source for some autumn sketches now located at the Cooper-Hewitt, although at the museum they are dated much later.[9] This summer sketching trip inspired several easel paintings, including The Wreck (1852, The Parthenon, Nashville, TX), and Home by the Lake (1852, oil on canvas, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN).

In 1852, he postponed a trip he had planned to South America, and instead visited central and northern Maine, including the Moosehead Lake region and specifically Mount Katahdin, Thoreau's favorite place deep in the heart of the Maine woods. In September, he took a brief visit to Grand Manan Island where he had gone the previous years, and then went back to Katahdin. On the way to or back from Grand Manan Island he may briefly have stopped at Mount Desert Island, as there are several sketches of turning leaves in his collection of sketches from Mount Desert Island, which could only have been done in September. This trip inspired several major easel paintings, including Mount Ktaadn (1853, oil on canvas, Yale University Art Gallery, CT) which was shown in the April exhibit of 1853 at the National Academy; Grand Manan Island, Bay of Fundy (1852, Oil on canvas, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT) which was shown also in the April 1853 National Academy exhibit and Coast Scene (1852, private collection); shown in the April exhibit of the National Academy the next year in 1854.

Sketching

In his early sketches Church concentrated on evidence of humanity in the civilization, and even an emblem of pride, representing one of America's most significant contributions to the early years of the industrial revolution.[10] In America, no landscape painter could avoid seeing sawmills, since almost every village had one. In Catskill, there were twenty-six sawmills along Catskill Creek, several of which Church sketched during his time with Cole. Even from his earliest instruction Church had been preoccupied with mills, as evidenced by his early sketchbook from his instruction with Benjamin Coe.[11] In 1845, he was copying mills from Cole's instruction book, and as early as 1845, he was putting mills in his oil compositions. Thus, this cultivation of the landscape was in his mind and his art early on, even before his teaching with Cole. With Cole, he learned to add nostalgia to this civilizing aspect, which we can see in two landscapes with mills after his years with Cole. Kelly points out that Church had been sketching mills since his time with Cole, but that they were of Church's favorite themes is evidenced by the existence of a dated sketch from his first weeks alone at Cole's house. In July of 1844, one of the first things he chose to sketch on his own at Cole's house upon his arrival was a mill. Later, in October and June of that year he sketched entire landscapes of the same subject.

In Maine, sawmills inundated the area because of its large timber and powerful water supply. In 1837, Thoreau noted two hundred fifty sawmills on the Penobscot River and its tributaries. In 1838, Bangor was considered the 'lumbering capital of New England". [12] In the early trips Church sketched several mills, and as Cole had sketched a similar mill near Mount Desert, this may have provided inspiration for Church to look at the same subject. Clearly Church was aware of the local industry and civilization, as his contemporaries like Lane also painted lumbering on the coast. Thoreau was struck by the transformations of the woods for civilization: "strange that so few ever come to the woods to see how pine lives and grows and spurts, lifting its evergreen arms to the light- to see its perfect success, but most are content to behold it in the shape of many board boards brought to market and deem that its true success." In his finished compositions from these early trips, Church never chose to include the buildings from his sketches; the sketches perhaps belie his real attitude towards progress.

Thus, contrary to Kelly's theory that Church sought out civilization, his sketchbooks instead suggest that he came to Maine precisely to look at nature away from humanity. If any of Church's sketches from the island are of pure wilderness, trees found naturally on the island, not things made by humans. Where his early sketches at Cole's house had been of farm animals, buildings and people, interspersed with trees, in Maine he found his own preferences in sketching, developing habits which would continue into the future moving away from people towards natural phenomena, rocks, cliffs, trees, skies, using words to describe the scene often in a color-by-number type of way. Yet following in the footsteps of his teacher and contemporary artists, his works in this early stage show that he still was focused on finding a civilizing feature in the landscape and was not ready to move completely into painting the wilderness for wilderness' sake, regardless of his intentions.

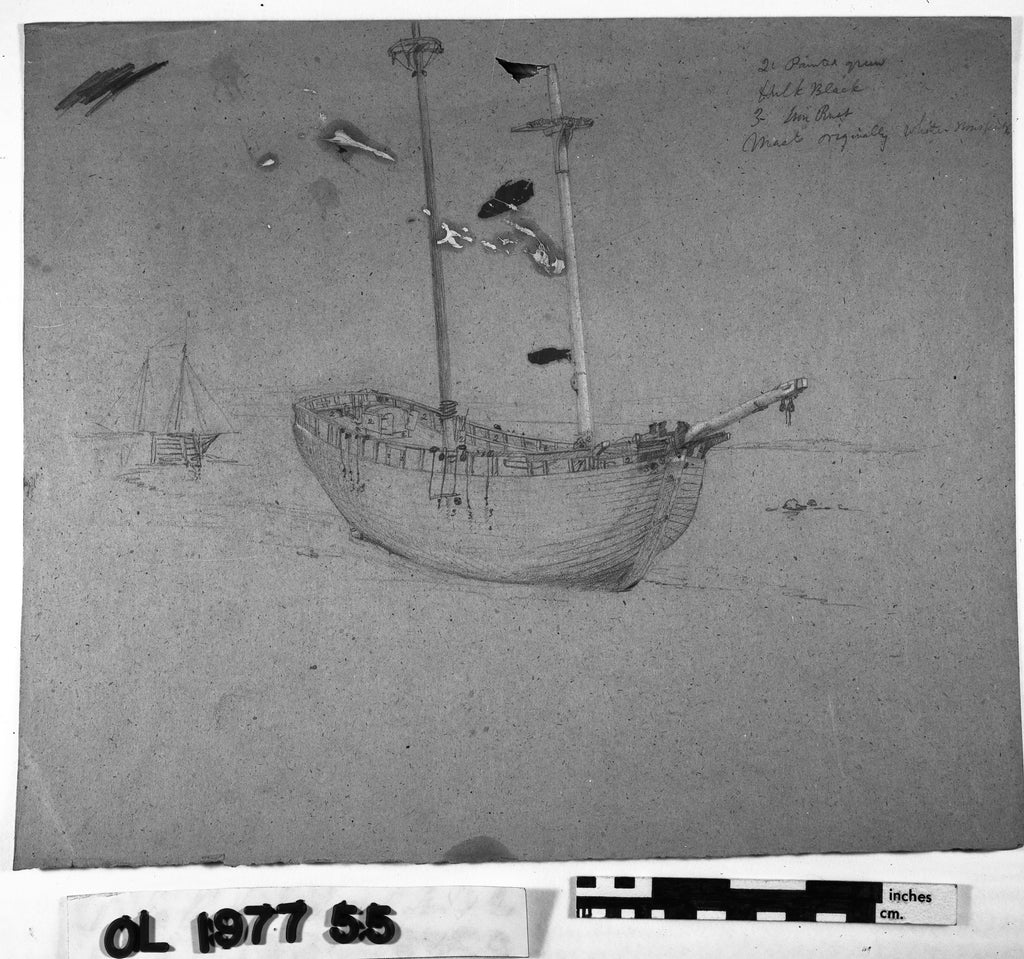

In the early trips Church split his sketches between evidence of civilization in Maine and pure natural phenomena. The majority of the former are of boats which caught his fancy as they passed. There are several sketches of sailboats, rough sketches of figures in boats, of a fleet of mackerel fishers, and of sailboats actually riding waves. Most of these boat sketches are rough, but a detailed sketch of sailboats Beached Sailing Vessel, (figs. 1 and 2) shows that Church certainly was capable of painting such physical objects in detail if he chose.

Beached Sailing Vessel, Fig 1

Beached Sailing Vessel, Fig 2

More often than not Church chose to focus on trees, cliffs, and isolated waves. Of the sketches specifically dated by Church from 1850 to 1852, the majority are of views of the mountain range and coastal cliffs from different areas he traveled to on the island. He made several detailed studies of trees, and was interested in various sizes and species, including Birch (fig. 3) and Evergreen Trees (fig. 4).

Birch (fig. 3)

Evergreen Trees (fig. 4).

The sheer number of surviving sketches of cliffsides show how impressed Church was with the rock formations. Olana alone has over seventy sketches from late July through mid-September 1850 during his first stay on the island, several focused only on the rocks and cliffs, for example Coastline Cliffs (fig. 5).

Coastline Cliffs, Rock and Surf (fig. 5)

In August 1850 he made several sketches of the Porcupine Islands and of Mount Desert Island from the Porcupine Islands. He was also impressed with Schooner Head and Great Head, and intrigued by the natural caverns, making several sketches from inside these caverns (see fig. 6).

View from Inside a Cavern (fig. 6)

His interest in the sharp and steep jagged cliffs along Great Head and Otter Cliffs are echoed in his later sketches of the scenery he found at Grand Manan Island, and in his use of these rock formations in his finished Grand Manan Island oil painting.

In his finished paintings, Church used these sketches to comprise scenes in which man is settled peacefully into nature, as well as scenes where nature is threatening, even conquering man. The common feature of his paintings from the island is the precision and detail with which he captures the surf and the rock formations, in their jagged edges and in their color. For a painter known for his skies it is rare to find oil paintings, such as Rough Surf, Mt. Desert Island where the horizon is completely lacking and the whole composition is filled by the water and the waves. Fog, off Mount Desert which was submitted to the Art-Union in 1851, is also unusual for its more than three-quarter canvas devoted to the ocean, with only a small strip for the sky and not nearly as much precision and detail or color used for it. In this early stage, Church was certainly experimenting to find his specialty, and in his early trips focused his interest intently on waves and the effect to surf in the several studies and oil sketches mentioned above, as well as in the unpublished studies.

Otter Creek, Newport Mountain

The early paintings of Maine's wilderness are also unique for the prominent positioning of a figure in the land, serving the same purpose as a boat in his seascapes. In later pictures, the figure either plays a lesser role or is left out entirely, as is the boat. Cole had included figures for scale, to give a greater sense of the sublime, of man's fallibility when faced with nature. Church's figures and boats seem to show instead a hope for redemption, a contemplation of nature, a more Thoreau-like appreciation for nature rather than a warning or religious message. Figures were an important final element in the early compositions, a trait he learned from Cole; but the focus of his sketches on these early trips was clearly his favorite aspects of the landscape, headlands and mountains, including Great Head, Otter Cliffs, and Schooner Head, and Dry and Newport Mountain.

Church compiled his finished paintings in his studio from specific studies of his favorite parts of the island. Newport Mountain is clearly identifiable as based upon the study Newport Mountain, Mount Desert Island (fig. 7).[13] Church's final composition takes elements from this sketch and demonstrates how he compiled his sketches into finished compositions. But unlike Home by the Lake or New England Scenery, in the paintings from Mount Desert, features and specific geographic points of interest keep their shape and position and are identifiable by name. In Newport Mountain, Church has positioned his vantage point to include his favorite spots and views of the island. Again, Church focuses on Dry Mountain notch, as with Otter Creek, Mount Desert. From a different angle, the notch of Dry Mountain rears its identifiable contour in the background, while Otter Cliffs in the left distance peak out from behind Schooner Head. These were Church's two favorite headlands, and he visited and sketched them the most frequently, including the striking study Schooner Head, Red Rocks (Fig. 8).[14]

Newport Mountain, Mount Desert Island (fig. 7).

Schooner Head Rocks (fig. 8).

Church frequently sketched Otter Cliffs during the early 1850s, and it was the subject of his last great painting from Mount Desert Island, Coast Scene. He may have been intrigued by Cole's Otter Cliffs sketch of 1844, the basis for his oil painting Frenchman's Bay, Mt. Desert Island, Maine.[15] Church made several other studies from the area around Lynam's Farm, just to the north of Schooner Head, which he eventually included in Newport Mountain. Church doubtless knew of Lynam's from Cole, who had moved there on 3 September 1844,[16] where he sketched Schooner Head and scenes from Great Head. Cole was obviously impressed with this scene, as he wrote that the walk from Schooner Head down to Sand Beach was the "grandest coast scenery we have yet found." On his sketch from Great Head, he wrote ''This is a very grand scene. The craggy mountain, the dark pond of dark brown water - The golden sea sand of the beach and the light green with its surf altogether with the woods of varied color - make a magnificent effect such as is seldom seen created by the sun.”[17] Whereas Cole did not actually sketch Great Head, he described it as "Sand Beach Head, the eastern extremity of Mount Desert Island... a tremendous overhanging precipice, rising from the ocean with the surf dashing against it in a frightful manner."[18] On his first trip, Cole's sketches of the island would have been foremost in his mind; it makes sense that Church's sketches that resemble Cole's, those of Otter Cliffs and Great Head, as well as the one of the same beacon off of Seal Harbor on East Bunker's Ledge which Cole sketched, are from the period of the early trips to Mount Desert Island, and probably in 1850.

On this first trip to Maine, Church devoted one of the largest groups of drawings to the mile long stretch of coast on the southeast side of the island, reaching from Great Head north to Schooner Head, with the Lynam farm on an inland slope of the rocky headland where Church stayed. Church sketched Schooner Head several times in the early 1850s and on the 1850 trip. As always, Church's attention to detail and description is paramount. In one sketch of the headland, Church included the small Lynam farmhouse, with nearby trees and a small area of pencil point dots labeled number ''2" in the key, meaning "pebbly beach." Like Cole, Church wrote annotations on several of his sketches, as an aid to his recollection of the visual facts. On Schooner Head, Red Rocks (fig. 8) he wrote "Red Rocks- Beautiful reflected light on M(iddle) Rock Separated more than right." This portion of the island was probably the terminal push of the ice age, and Newport Mountain and its studies show how intrigued Church was by the juxtaposition of rising vertical cliffs and the horizontal horizon.

On his 1855 trip, Church took his friends to see Schooner Head, and Tracy's visual description of it gives us an idea of the impression the immense cliff wall made on Church as he climbed to the same spot:

We came up the to the precipice which overlooks the ocean. This portion stands out into the sea, and is formed with a craig point of about 75 feet in height, battered, and furrowed by the eternal dash of the waves, and jagged into all kinds of notches, and criphts (sic) and towers. Strolling over this wild brink we passed around the projecting head, and reached a frightful chasm, the neck front seems to have split off and moved a few feet into the sea, leaving a ghastly fissure and the outer wall thus formed has a natural door way opening through from the se to the fissure. W crept down the natural steps outside of this guard wall, and passed through the arched doorway to the bottom of the fissure, where every wave washes up and retreats by the side of our very steps.[19]

Red Rocks, with its notations, shows that Church was extremely interested in geology not only for the formations but for the color of the rocks, and his oil sketches are often painted with a rust-colored ground, still evident in some unfinished sketches. After the ice age, the later periods of erosion and sedimentation left rock stratifications, broken into jagged outcrops, and usually colored brown by their iron-oxide content.33 Church was intrigued by these various colors of the geological formations, and consistently labeled them in small outlines filled in with a number, creating abstract forms. His key in Cliff wall Near Great Head (Olana, pencil on paper), notes the "dark streaks " of the tidal line on the rocks, and "rocks of every possible color."

This attention to detail, so typical of Church, translates into paintings with precise color and rock formations often overlooked in the general academic thesis that Church invented the compositions of his paintings, which he did not. Although he annotated his sketches as precisely as possible, Church did occasionally take license with the foreground of his compositions from Mount Desert Island. Yet unlike his other finished paintings, those from Mount Desert Island are the least composed in terms of artistic license. For instance, Cole's cabinet sized painting House, Mt. Desert Maine (pencil on paper, Olana) is typical in that it is a composite of settings from the many sketches he made of the surrounding mountains. It is a generalization of an experience of a particular scene. The viewer cannot determine exactly where it is, thus it is every man's experience.

With Church, however, the specificity of place is central to the painting, and the figure includes the viewer in a particular moment and experience of time. Church's work increasingly became geared to specific experience, whether the calm gaze in Otter Creek, or the man struggling with nature in Newport Mountain. The themes are reminiscent of Cole's --man at peace in nature, man struggling against nature's force-- and in his final composition Church, like Cole, adjusts elements of the landscape. In these early Mount Desert paintings, however, the compositional elements and purposeful story give way to an appreciation for the exact moment, as though no embellishing was necessary, unlike Cole's adjusted perspective for added drama in Frenchman’ s Bay. In contrast, Church remained remarkably true to the real forms and perspectival distances, even altering the direction of his gaze in Beacon, to keep the beacon in its accurate position looking Southeast.

Wilmerding calls the figures in Otter Creek and Newport Mountain "storytelling details that recall Cole's art.”[20] Unlike Cole's figures, however, Church's lend specificity to place, they are more than storytelling, more than details used to achieve a moral message, and increasingly become unnecessary to Church. For him, the figure's true purpose is to be the viewer, not to provide detail for a story; thus, as it becomes increasingly possible to imagine that we can enter Church's pictures, the figure's role becomes unimportant. The viewer does not need a figure to understand this, and so by the time of Coast Scene, Church omits them entirely. This disappearance of the "storytelling detail" as unnecessary in the great scheme of the canvas in its particularity is first evident with Church's Beacon, one of his greatest successes from the first trip's work.

Church view of the wilderness progressed so that figures became unnecessary. His paintings became about specificity, here and now, rather than general experience and morals. The viewer did not need the extra step through another figure in the painting, the typical entry point in the past. Rather, the viewer could enter immediately, and this immediacy of feeling becomes clear with Beacon and becomes Church's preoccupation as he focuses more on his favorite and his most specific vistas of all- capturing one moment in time in a sunset. To transport the viewer to this immediate place was Church's special gift and one that was recognized by his critics. Of Beacon, one critic wrote that the picture was "worth almost as much in the sensations it produces, as a visit from the hot city in August to the still, cool sea- side.”[21] This was something Cole never learned, because his paintings were always one step removed from the viewers, for "storytelling" rather than for immediate experience.

Church learned this lesson painfully through criticism. At the first major showing of his own work, after the first Mount Desert Island trip, his story telling painting The Deluge was a failure, with its focus on figures in distress; yet, this painting is precisely what Wilmerding means by "added human action to the natural drama" Instead, Church's most successful paintings were those with only the natural drama, natural phenomena, such as Beacon and Newport Mountain, where the figure is an intermediary, not a barrier, to the immediate experience.

The Deluge and The Wreck

The mills, houses and people in Church's early pictures show man cohabiting with a nature unlike the fierce nature of an angry God more typical of Cole's allegorical work. Only two paintings from the early trips attempt to show this type of natural dominance, and neither were received with much success. The first was The Deluge (location unknown). Although unlocated, we can tell some idea of its appearance from two oil studies, which are quite detailed as this was intended to be the most important work of the 1851 submissions. It was certainly the largest, measuring 48 x 68 inches. Mount Desert Island provided ample waterpower to study for the torrential power of The Flood, and elements of its composition were gleaned from his coastal studies of 1850. A contemporary description from a journal describes the painting, and it is easy to imagine how the studies and scenery from Mount Desert Island made a backdrop for this allegorical flood:

In the foreground, upon a crag which is just about to be torn by the rushing water from the side of the mountain, are a woman and child and a tiger, who have sought refuge the from the torrents. The rain falls in overwhelming sheets, while the lightning and a lurid sunset add to the terrors of the scene.[22]

Interspersed with Church's 1850 sketches from his first trip are the studies from The Deluge (figs. 9, 10), which leads one to believe that he conceived of this scene and was inspired to depict its violent forces of nature using elements from the geological formations at Mount Desert Island. The scene depicted a theme Cole might have suggested, and a popular subject of many painters of Cole's generation. In fact, Cole's main easel paintings from Mount Desert deal with the harsh conditions of nature in its sublime state rather than the civilized peaceful nature Church most often depicted in his first subjects. Although this picture deals with the violence of the ocean and the powerlessness of man, its composition and handling of light and paint is more like Lane in his luminist style.[23]

Mother and Child from The Deluge (fig. 9)

Study for The Deluge (fig. 10)

Exhibitions and Criticism of the Mount Desert Paintings

Most of the major paintings exhibited by Church in his early years were based on these summer sketching trips to Maine, and their popular and positive critical reception ensured his success as a landscape painter. The major venues of exhibition for the New York public were the National Academy and the American Art-Union, at both of which Church exhibited regularly throughout his career. The National Academy and had annual exhibitions in April, for which artists could submit works for acceptance. There Church exhibited The Deluge and Lake Scene in Mount Desert, in 1851; The Wreck and Home by the Lake in 1852; The Natural Bridge, VA, Mount Ktaadn, and Grand Manan Island, Bay of Fundy, in 1853; and A Country Home and A New England Lake in 1854. The reviews of these exhibits usually had the most current and respected art criticism, and it was a long standing venue for the culturally aware public to view the foremost American painters of the day.

The second major venue was the more recent American Art-Union, an organization with members all over the country, but mostly New England, through subscription. It was extremely popular, and Church noted 8000 subscribers, generating $40,000 in 1847, which grew to "18 or 19 thousand" by 1849.[24] The new approach to distributing art was more democratic than the old-fashioned patronage Cole was used to. The organization would collect its subscription money and use it to buy paintings which were then distributed by lot to the members at the end of the year in December through a type of auction. The American Art-Union also produced a bulletin with reviews and notes about artists and their works. The American Art-Union auction in December 1851 sold Church's The Deluge, Beacon, Fog off Mount Desert, and New England Scenery. 1851 also marked the first showing of Church's works at a major venue outside New York City, when James Lefevre, a traditional patron who bought four cabinet size paintings, sent two of them to the annual exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. These may have included Otter Creek, and Twilight.

Beacon also received praise for its sea atmosphere and rendering of expansiveness which brought this quality before the public in a way in which it had never been before. When the focus was on the picturesque, the scene had to be framed like a picture. Now Church took the frame away, and let the public see beyond infinity, on that endless horizon where the naked eye could only pick out half a fleet of mackerel boats. Such great expanses were unimaginable in the midst of the city. Church took away the person in the foreground, or the tree, or composed image, and painted a true symbol. The reminder of human presence was far in the distance, in the form of a boat on the horizon, a reminder of humanity- small and unobtrusive in this great wilderness. Yet the subject of this painting, unlike New England Scenery, was not scenery, not "storytelling details," or wilderness per se. It was limitless horizon and limitless expansiveness- a new kind of image for the American ideal. When the landscape painter met the ocean in Maine, his imagination could go beyond cultivated or raw wilderness into something even purer. A beacon, built to guide human explorers, stands for humanity, but it is in a great expansiveness that cannot be conquered. Church, the explorer, is guided by the beacon to bring the ship to shore safely, to bring this expanse and experience to the American public. With this picture, Church changed the issues, the dichotomy of nature versus progress.

Human presence was metaphorically there in the beacon for man; but the idea was not the tug between nature and civilization, as in the happily cultivated New England Scenery, it was about the infinite sea and the ever-changing sky, elements which humans could never hope to alter. Critics understood this ability of Church's painting to bring the public beyond their city lives into this expansiveness of true wilderness, and the sea, which had not before been a subject of Hudson river painters in this raw and wild way.[25] One critic noted that "he is to show in the splendid play of the light, and air, and clouds, that which we do not see, or seeing, do not perceive." The critics appreciated that Church allowed people to see things not possible in the mid-nineteenth century without a trip. The work was "worth almost as much in the sensations it produces, as a visit from the hot city in August to the still, cool, seaside." Yet another critic wrote: "As the spectator looks, he muses, and the sea and the shore and their eternal mystery and sadness gather in his mind.” Already, viewers sensed the melancholy and nostalgia Church took from the picturesque and translated into American's own great wilderness; melancholy not for the past but for the wilderness mingled with the excitement of the great vastness for America.[26] This would be explored in later skies and wilderness scenes, such as Twilight in the Wilderness and Sunset.

Critics appreciated Beacon in a way that they could no longer appreciate the allegorical works they had been seeing for so long with Cole. Beacon and The Deluge were Church's two major works in the spring exhibition at the National Academy during 1851. The comparison they afforded critics between Church's two styles, the old style he was moving away from and the new, dramatic wilderness style, were not lost on his audience, nor on him; for after the failure of The Deluge Church spent the next decade focusing on wilderness subjects. One critic wrote of Beacon that it was "a strong and truthful picture, with more imagination in its reality than the effort at the Deluge by the same artist.”[27] The Deluge, clearly a return to the allegorical style of Cole, was the most "resounding failure" of Church's early career, made more acute by its comparison with the success of the other submission, Beacon. From the existing studies Church made from 1850 of waves on the island, it is obvious that Church carefully studied the elements of torrential and powerful water to express them. Yet clearly the public could no longer appreciate painting as truthful to nature unless it was realistic. Despite Church's careful nature studies, one critic found fault with The Deluge because of its lack of truth to nature: "Had Mr. Church seen the deluge, he would no doubt have painted it to better advantage.”[28] This type of criticism is more acute when compared with the that of its neighbor, the Beacon, which was noted so much for its truthfulness to nature that it could literally transport the viewer to the scene.

In 1851 the American Art Union also printed an anonymous letter, almost certainly submitted by Church, praising Mount Desert as a place for landscape painting. Church's description of seeing Mount Desert Rock and small sailboats on the horizon is much like Tracy's experience from the peak of the tallest mountains. Church wrote to the Art-Union Bulletin: "from the highest peak... we could easily see Mount Desert twenty-five miles off in the ocean; and the mountain on which we stood is seen sixty miles at sea... Far out in the offing, the soft, hazy, blue floor of the ocean was studded with nearly a hundred white sails of fishing smacks.”[29]

Church's early years in Maine provided him with the success and confidence to return several times and continue to perfect his landscape images. His critical reception was largely positive, and the inconsistencies in his attitude towards American progress and its effects on the wilderness had little impact on the success of the pictures. His commercial takeaway was thus that the pure landscapes, whether with people or of nature, were more successful than Cole's old style of allegorical or blatantly religious paintings. Church's paintings appealed to the public because they addressed pertinent issues to American nationalism and identity, without screaming the message, as Church himself was unclear of any message himself. In his next years, he began to concentrate only on wilderness scenes, on new territory, and on exploration, focusing more on the natural phenomena itself rather than including people or houses. This spirit of pure adventure is seen in his increasing trips to foreign places in search of ever more spectacular skies and landscapes and geological phenomena.

Church's exploration of the untamed wildernesses of America and other countries lends weight to this theory, but his trips to Mount Desert and Mount Katahdin showed him trying to get away from civilized America. This contradicts Kelly's theory that Church had an ''unshakable commitment" to the vision that the "future greatness of American could only be attained through the efforts of its most industrious citizens," to use America's "natural bounty," and that it was better to do this "too soon" than to do nothing at all. Rather, Church may have painted scenes like New England Scenery because that type of cultivated wilderness and progress was precisely what America's "industrious citizens," Church's patrons, wanted to buy, whereas he increasingly went back to the raw wilderness, the unspoiled nature. This continued in his later visits to Maine in the heart of the woods, when he spent more time deliberately away from civilization and even bought his own piece of the wilderness to ensure its survival.

[1] Although several sketches from the 1870s and 1880s in the Cooper-Hewitt bear the identification Mount Desert Island on their catalogue card, Church did not label the sketches himself and the only documented travel to Maine after 1862 is to Mount Katahdin and Lake Milinocket.

[2] For more discussion, see Franklin Kelly, Frederic Edwin Church and the National Landscape (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988), 40, and 55-60.

[3] Ibid., 11.

[4] The Literary World, May 1847, quoted in Kelly, National Landscape, 12.

[5] Kelly, National Landscape, 12.

[6] Frederic Edwin Church to Aaron C. Goodman, 17 August 1850, Archives, Olana State Historic Site, Hudson, New York.

[7] These letters were unsigned, but Huntington convincingly attributed them to Church in David C. Huntington, The Landscapes of Frederic Edwin Church (New York: Braziller, 1966. Scholars now generally agree that they were submitted by Church during his first trip to the island. See Wilmerding, Mount Desert, 72; Kelly, National Landscape, 35.

[8] “Chronicles of Facts and Opinions: American Art and Artists,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union (November 1850), 131; quoted in Kelly, National Landscape, 36.

[9] The later dating seems impossible because Church stopped visiting Mount Desert after 1862, and his trips in the 1860s were not during a time when foliage would have begun to change.

[10] Kelly, National Landscape, 14.

[11] Ibid., 15.

[12] Wilmerding, Mount Desert, 78.

[13] The notes on colors in the margins read: “Grey green leaves most common, and Nearly all the trees are birches- white stemmed”.)

[14] Margin notes read: “Red rocks- Beautiful Reflected light on M. Rock”

[15] Traditionally the section of coastline in this painting has been identified as Otter Cliffs, but it is quite possible that it was inspired rather by Schooner Head. See Morison, Mount Desert Island, 44.

[16] Wilmerding, Mount Desert, 37.

[17] Noble, Life and Works, 270.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Tracy, “Log Book”, 15 August, 58.

[20] Wilmerding, Mount Desert, 85.

[21] “Twenty-Sixth Exhibition of the National Academy of Design,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union, series for 1851 1 May 1851), 23; quoted in Kelly, National Landscape, 40.

[22] Mary Bartlett Cowdrey, American Academy of Fine Arts and American Art-Union Exhibition Record, 1816-1852, New York Historical Society Collections, vol. 77 (New York: New York Historical Society, 1953), 72; quoted in Kelly and Carr, 60.

[23] The luminist style was glassier and more expansive, with cooler crystalline palettes, than the older Hudson River style of Cole’s generation. It began to be adopted by Lane during the time of his first trip to Mount Desert Island. Although some of Church’s paintings are in this style, he was never considered definitively as “luminist” as Lane, for example. For more discussion of this style, see Wilmerding, Mount Desert, 11,33,55,56; also, John Wilmerding et al., American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1850-1875: Paintings, Drawings, Photographs (New York: Harper & Row, 1980); also, John Wilmerding, Fitz Hugh Lane, 1804-1865: American Master Painter (Salem, Mass: Essex Institute, 1964).

[24] Frederic Church to Aaron C. Goodman, 24 December 1847, Archives, Olana State Historic Site, gift of Mrs. David M. Hadlow; and ibid., 17 December 1849, in ibid.

[25] Lane also painted the Maine coast, but his luminist pictures from the same period have a more mysterious, twilight and soft glow than the raw expansiveness of early morning and breaking day of Church’s first great ocean scene. Lane’s pictures from Mount Desert also tended to be smaller, cabinet sized pictures more typical to the Luminists.

[26] Wilmerding feels this is explored in Sunset and Twilight in the Wilderness; see Wilmerding, Mount Desert, 90.

[27] “The Fine Arts; The National Academy,” The Literary World, 19 April 1851, p. 320; quoted in Kelly and Carr, 61.

[28] Ibid., quoted in ibid., 60.

[29] Huntington, Landscapes, 31.